As Colorado grows, protecting what makes our home special is vital.

Join us in conserving the land and water that unite us.

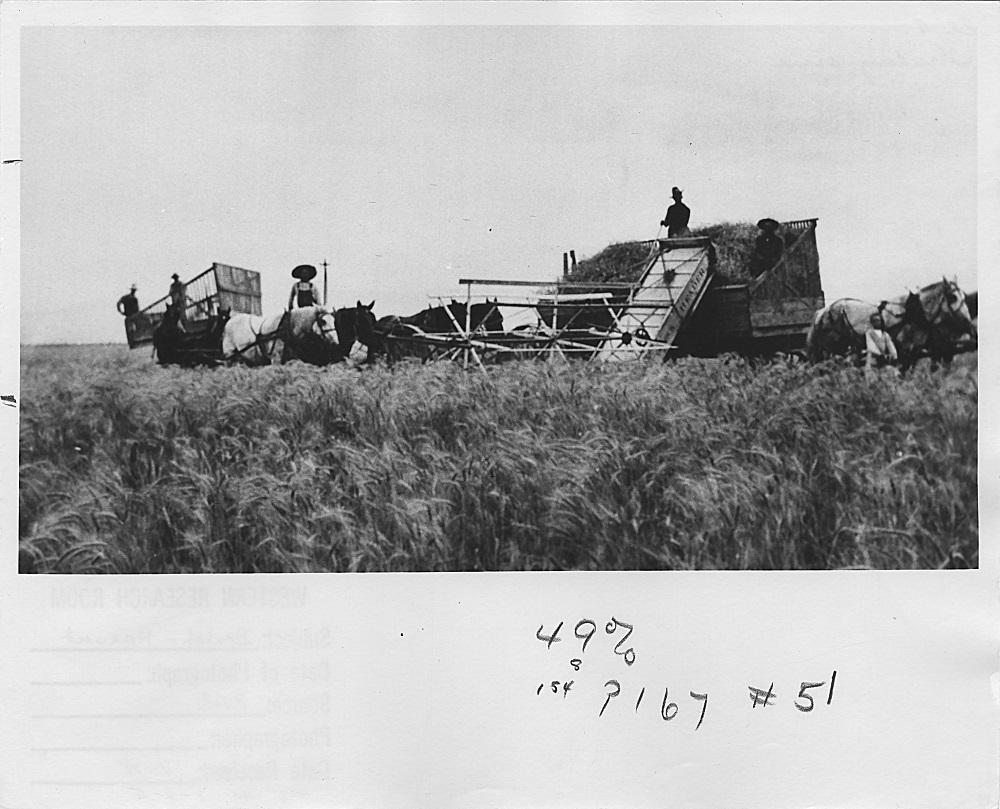

The development of agriculture over 12,000 years ago changed the way humans live. We transitioned from a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle to farming with more permanent settlements that provided a more reliable food supply. In Colorado, Indigenous peoples contended with limited precipitation by building dams, canals, and terraces to irrigate food crops in the desert Southwest, including parts of the Arkansas River Valley. When Anglo-Americans arrived in Colorado, they found plains tribes growing the three sisters: corn, beans, and squash. The Arkansas River marked the boundary between Mexican and U.S. territories, and Spanish-speaking immigrants settled along its southern tributaries—the Huerfano, Cucharas, and Purgatoire rivers—irrigating small patches of cultivated land as their forebears had done.

Commercial agriculture developed in the Pikes Peak region after gold was discovered in 1858. Once fortune seekers began to realize the difficulty of striking rich, many turned in their pickaxes for plows and focused on the fertile lands in the lower Arkansas Valley. It quickly became apparent that commercial agriculture would require irrigation to succeed, and construction of canals and ditches allowed farms to flourish in the drought-prone climate.

While population growth, drought, wildfires, and flooding continue to present challenges to those who steward the land today, agriculture remains a living tradition in southern Colorado communities. From the fertile farms of southeastern Colorado to the headwaters of the Arkansas River basin where cattle and hay ranches are nestled among the mountains, farming and ranching is essential to our economy, communities, and way of life in southern Colorado.

A heavy hitter in Colorado agriculture, Otero County’s Rocky Ford region is famous. Ask any Coloradan what they think of when they hear “Rocky Ford,” and they’ll tell you melons. The Rocky Ford cantaloupe has been a point of pride for the region for more than 130 years.

One of the founders of the Rocky Ford melon industry, George W. Swink moved to southern Colorado in 1871, where he quickly saw the region’s farming potential. Swink helped construct essential irrigation ditch and canal routes, transforming the region into an agricultural powerhouse. The dramatic day to night temperature fluctuations make Rocky Ford’s cantaloupe and watermelon some of the sweetest in the nation. Swink introduced honeybees in 1878, which proved crucial to pollinating mass amounts of melon crops, and established Melon Day, a festival which grew into the Arkansas Valley Fair, the oldest continuous fair in Colorado.

While focused on expanding production, Swink also paid attention to the development of quality, testing numerous varieties to identify those most appropriate to the lower Arkansas Valley. His efforts inspired others with more technical knowledge to devote their talents to local agriculture, and by 1926, farmers in and around Otero County produced 95 percent of all the cantaloupe seed grown in the U.S. and a large share of the watermelon seed. Today, melons remain the region’s pride and joy.

Best known as “Steel City” for its history of steel and rail production, Pueblo County has also been recognized for its premier agricultural lands for more than a century. Many of the family-owned farms in the county represent generations of families who have stewarded the land and helped solidify the county as some of the best farmland in the nation.

In 1868, while visiting farms throughout the state for Rocky Mountain News, Dr. William R. Thomas visited 86 farms along Fountain Creek near Pueblo. He found corn was the principal crop, followed by wheat, oats, barley, and other grains. As Dr. Thomas traveled around other farms in the county, including those in the Huerfano Valley, he found similar crop trends.

Historically, potato crops proliferated throughout Colorado, and in 1868, the Pueblo Chieftain reported that John J. Sease of St. Charles Mesa grew a potato weighing more than 2.5 pounds, part of a 150-bushel crop grown on 0.4 acre. But no discussion of Pueblo’s agriculture would be complete without mentioning the renown Pueblo chile. Brought to the area by Mexicans moving to the region, chiles enjoy a long, rich history in the county. Today, the most popular strain, the Mosco, is a more recent development.

Released to growers in 2005, the Mosco chile was developed from Mira Sol plant stock by Dr. Mike Bartolo, a vegetable crop specialist with Colorado State University (now retired). Dr. Bartolo developed the Mosco chile from seed stock given to him by his late uncle, Harry Mosco (for whom the chile is named), a farmer on St. Charles Mesa.

Thick fruit walls makes the Mosco ideal for roasting, the traditional method for preparing Pueblo chiles, as it is less prone to splitting during roasting, ensuring the juices don’t seep out and evaporate. As a result, Mosco chiles maintain their rich flavor much better than other strains. One of the largest events in southern Colorado, the three-day Pueblo Chile & Frijoles Festival, celebrates Pueblo chiles and Pueblo County agriculture.

In addition to chiles, crops like corn, beans, pumpkins, squash, beets, watermelons, cantaloupes, and hay are also staples grown in the county.

As Thomas continued his 1868 tour of Colorado agriculture, he observed 66 well-developed farms on Beaver and Hardscrabble Creeks in Fremont County. As in Pueblo County, corn was the principal crop at that time, with wheat ranking second. Just a year before Thomas toured Fremont County, W.C. Catlin planted the first fruit trees on record in the area. Costing more than $500, these expensive trees were delivered across the plains via wagon; however, very few survived into the 1920s. It wasn’t until Jesse Frazier’s efforts to establish apple trees that fruit production took hold in the region. His apple orchard became the largest in the state. In 1888, more than 720,000 pounds of fruit was shipped from the county, including apples, pears, grapes, plums, peaches, strawberries, and more.

By 1926, the Upper Arkansas Valley was considered one of the state’s more important regions for commercial fruit production, and orchards in eastern Fremont County continue to produce a variety of fruit, thanks to enduring enterprises like Colon Orchards in Cañon City. The county also produces grapes, as well as other vegetable crops, and beef.

After President James Buchanan signed an act creating the Territory of Colorado, El Paso County became one of the original 17 counties created by the Colorado legislature in 1861. The county seat was located in Old Colorado City (now part of Colorado Springs), which sprung up in 1859 and boasted more than 300 dwellings by 1860. William Campbell, Hubbell Talcott, and John Bley built cabins along Fountain Creek and diverted the waters to support farmers, creating the first local water rights.

Irrigated farming in El Paso County has always been tricky. In 1865, El Paso County agriculture experienced the devastation of a “grasshopper year” with swarms not only devouring crops, but also eating leather, wood, and wool. Given the level of toil required to irrigate and raise crops in the area, local residents were so dismayed that they halted work on the Ute Pass Road, deemed important for connecting agricultural producers with the mining districts.

Even after the grasshopper year, raising crops proved problematic. Farmers suffered another bad year in 1888 from a combination of drought and early frost, and no fruits were harvested that year except in the Fountain Valley where irrigation was possible.

Nonetheless, farmers persisted and eventually managed to grow wheat, oats, barley, rye, corn, potatoes, timothy, clover, and alfalfa without irrigation. However, irrigated acreage yielded 572 bushels of fruit, including 150 quarts of blackberries, 5,795 quarts of currants, 2,170 quarts of raspberries, and 890 quarts of strawberries. Animal byproducts, such as meat, cheese, butter, and honey, were more productive. In 1888 El Paso County produced 90,500 pounds of cheese, 83,655 pounds of butter, and 4,125 pounds of honey.

Teller County was formed from part of El Paso County in 1899, the result of political differences between miners in what is now Teller County and mine owners, many of whom lived in Colorado Springs. Though once an important lettuce-producing county, its main crop today is hay, primarily for beef cattle, with a few farmers raising crops like beets, radishes, and hops.

At present, El Paso County’s annual farm commodity sales exceed $31 million with Teller County sales at over $1.2 million. Statewide, El Paso ranks third in raising horses, goats and chickens; first in production of nursery stock; and second in sod production.

In the 1920s, Buena Vista became known as the “Head Lettuce Capital of the World.” Lettuce is well-suited to Chaffee County’s short growing season, and Buena Vista benefited from other favorable conditions—ice and transportation. During winter and spring, workers cut large blocks of ice from Franklin Reservoir, better known as Ice Lake, which supplied millions of pounds of ice that kept lettuce cold during transport to East Coast markets via the nearby Denver and Rio Grande rail line.

G.D. Isabel deserves much of the credit for Chaffee County’s once-burgeoning lettuce industry. In 1918, he rented 10 acres on the Burleson Farm near Buena Vista. Later that year, he harvested enough lettuce to fill a train car, earning him approximately $7,000. By 1921, local lettuce growers had organized the Colorado Co-operative Lettuce Growers’ Association at Buena Vista, which also handled other produce like peas and cauliflower.

Lettuce is still grown in the region, along with produce like squash, carrots, broccoli, and herbs. Farm commodity sales in Chaffee County total $12,237,000 annually. But now hay, including alfalfa, dominates the county’s crop production, and most of the hay which supports the area’s cattle ranching. In business for 70 years, Scanga Meat Co. continues to process local livestock, supplying retail clients as well as restaurants across the region.

In 1924, Custer County was once counted among Colorado’s major lettuce-producing counties along with Chaffee, Teller, Fremont, and Eagle Counties. By then, Colorado had increased head lettuce production to 5,600 acres, earning growers $975,000. The following year, lettuce-growing acreage almost doubled to 10,500 acres with a crop value of $2.1 million. Other high-elevation vegetable crops included cauliflower, peas, and spinach.

Today, Custer County’s days as a lettuce producer have gone, replaced by hay, which supports an active ranching community. The county also has 38 active honeybee colonies.

Huerfano County’s modern-day agricultural roots stem largely from Hispano shepherds moving into the area in the 1860s from the San Luis Valley, bringing sheep grazing into the region. But by the turn of the 20th century, much of the rangelands were purchased by Anglo-American ranchers. Today, Huerfano County’s primary commodities consist of hay and cattle.